In March 1993, I interviewed Father Alexander Mumrikov, a Deacon of the Russian Orthodox Church, during a visit I made to Moscow. We met at the offices of Inward Path, a magazine devoted to human development. The interview was arranged by the editor of the magazine, and was handled through an interpreter, the deputy editor of the magazine.

I had first heard of Father Alexander when I accidentally ran across the English edition of Inward Path in my local magazine store. I was especially fascinated by Father Alexander’s background: he was educated as a physicist, specializing in charged particle accelerators and ultra high frequency energies. After graduating from Moscow University in 1970, he went through many changes. He worked as a physicist, studied Tibetan and other Eastern philosophies, wrote articles on icon painting at the Andrei Rublov Museum, and modeled the atmospheric environments of the planets. He became an altarist in the Russian Orthodox Church, headed the department of theology and Bible studies for the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate, and lived for a time at the monastery of St. Balaam in northern Russia.

In 1990, Father Alexander formed the “Commune of the Life Giving Cross of Our Lord.” At any one time this community, which Father Alexander calls a “family,” had 20 or 30 people attending meetings. Participants—who include both Christians and non Christians—did not live together (“the Soviet authorities would not allow it,” says Father Alexander). They came together twice a week in groups not only for communal prayer, but also to share their experiences, knowledge, and questions arising from their experiences every week in the Russian Orthodox Church, or some other temple. The rest of the time they simply lived ordinary lives.

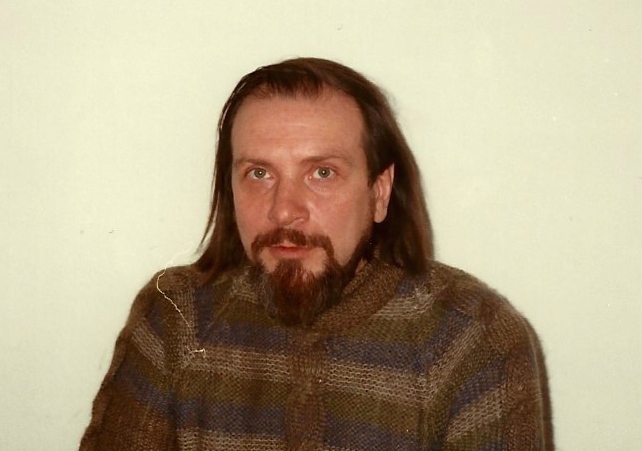

My interview with Father Alexander took place through the interpreter. A gentle, soft-spoken man, Father Alexander professed to know very little English; I felt at times, however, that he understood what I said before the interpreter had a chance to translate for him. This was later confirmed when I hired a Russian translator to listen to the tape. Father Alexander would often correct in Russian the interpreter’s version of what I said.

Q: In your interview in 1992 in Inward Path, you said that in order to get in contact with a higher being, “you’ve got to know his language.” You pointed out that in the Russian Orthodox tradition, that language is prayer—especially the Prayer of Jesus: “My Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” You also said that in former times Russian monks combined the Prayer of Jesus with breathing exercises and kept repeating the prayer throughout the day, and that this enabled them to awaken their spiritual hearts and tap into the highest spiritual energies. Is it important to say and feel the Jesus prayer in a certain way to make this possible?

A: Since each word of the Prayer of Jesus is connected to a certain energy, many difficulties and dangers are associated with it. [It was clear that Father Alexander was reluctant to say very much about the Prayer of Jesus.]

Q: Then how should one approach the prayer to benefit from it?

A: A simple example. Orientation at the level below the chest may bring the person not to God but to an exaggeration of sexual feeling.

Q: How can one avoid this?

A: First of all it is advisable to focus your attention about two fingers above the heart, in the center of the chest. If the process becomes too intense, you should move you attention more to the right side of the chest. The right side is associated with the center of the will. In the sacrament of christening, we are concerned first of all with balancing the will, which has been unbalanced through Adam’s sin. Gradually the process moves into the center of the chest, from right to left and left to right, and then it rises to the level of the throat. There one experiences a special feeling, an opening; one senses a kind of chalice opening upward—the same chalice that is turned upside down in the church. The chalice includes an “apple,” so called by art historians, which corresponds to the throat and through which takes place the transformation of energy from the level of the chest to the higher centers in the head. The chalice represents the spiritual development of man. The first sphere is formed at the level of the chest, at the time of prayer. The second sphere is compressed at the level of the throat. And the third sphere opens in the head.

Q: So the icons and chalices of the Church are symbolically related to energy?

A: Yes. They represent the science of those people who have learned how to direct their energy. They are able to feel the chalice in themselves and to watch the transformation of energy as it takes place. There are not many such people, and in general the process is a very difficult one. It is connected to the gift of tears of the monastic tradition. When this process begins, a person has difficulty communicating with others. He really feels as though his soul is separating from his body. The process is extremely slow and painful, for many deep changes at the level of energy take place. A person who is unable to be aware of this process, or who is unable to master it, may become physically or psychologically ill for a very long time. In most cases, the process must be guided by someone who has already gone through it. A necessary condition for the traveler on the spiritual path is that he must totally obey the guide.

Q: [Asked during another point in the interview.] Doesn’t the demand for obedience raise the problem of the conflict between the authority of the church and the authority of inner realization?

A: The pressure of authoritarianism appears when there is a problem of personality. In Russian Orthodoxy, the personality has no authority. A special psychology exists which is the opposite of Western psychology. It is connected with the transformation of consciousness so that it is not authoritarian. It is the tradition of the love of the good.