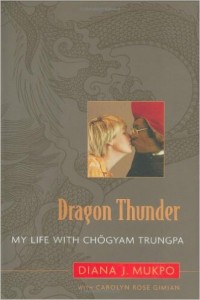

Dragon Thunder: My Life With Chogyam Trungpa, by Diana Mukpo & Carolyn Gimian

Dragon Thunder is a significant book on many counts. The book not only gives us a close-up, no-holds-barred view of the extraordinary life and work of Chögyam Trungpa, one of the great spiritual teachers of the 20th century, but it also shows, without equivocation, some of the many both serious and humorous complexities and paradoxes and challenges involved in Trungpa’s “crazy wisdom,” and his relentless efforts to bring Buddhism to the West.

Diana Mukpo’s intimate revelations as lover, wife, friend, and student of this remarkable human being and teacher are not only lovingly and courageously expressed, but, perhaps just as important, they are also balanced and far more objective than one might imagine.

You don’t have to be a Buddhist to appreciate the wisdom that permeates this book; you only have to be willing to see beyond the framework of your habitual self-image and your belief in “spiritual correctness,” and open to the miracle and mystery of your own being. Of course, that’s a big “only,” which will perhaps be difficult for those who would rather dwell on Trungpa’s so-called scandalous behavior (of which there are many possible examples in this book). At the very least, Trungpa’s life was unconventional, and for many, especially those who haven’t yet seen into or discovered their own dark sides, that can be threatening. As Diana Mukpo writes, “Rinpoche lived his life without the conventional reference points that most of us cling to as the anchors of our sanity.”

Though I was never a student of Trungpa’s (I was deeply involved in another teaching at the time or I might well have been), I was fortunate to hear him speak on many occasions in San Francisco and Boulder, and even asked him questions important to me at the time. No matter what his apparent state (drunk, sober, in pain, or whatever), his answers always helped open me to myself in a new and more-honest way; he was one of the most insightful human beings I have ever met. Above all, as this marvelous book so clearly shows, he never hid from or tried to bypass the messiness and uncertainty of being alive on this planet, but rather faced it with full vulnerability and awareness. And, so far as I can tell, he demanded the same from his students in the many often difficult and seemingly “crazy” conditions that he created for inner and outer work.

I remember seeing Diana (though I didn’t learn who she was until after the meeting) once in Berkeley CA (sometime in the 1970s), when she got up from her seat in the front row of the meeting room while Trungpa was speaking and walked slowly over to a nearby cold drink vending machine off to the side of the room. As I continued listening to Trungpa speak I heard the very loud sounds of the coins being deposited and the beverage container hitting the floor of the open compartment at the bottom of the machine. I watched and listened as she withdrew the drink, opened it, and returned to her seat. And I saw how quickly and easily I got lost in the judgmental thoughts that went racing through my mind: “How dare she interrupt the meeting in that way; she must be totally unconscious of what is happening here tonight; even I know that one should remain quiet while the master is speaking”; and so on. Of course, Trungpa simply kept speaking, seemingly undisturbed by her actions. I must say that I learned a huge lesson about inner freedom (and especially my lack of it) that night.

Toward the end of the book, the author gives us a direct insight into her own heart and the transformative influence that Trungpa had on her: “I know that for me, I will continue to long for him, as long as I have breath. I am left, however, not only with a broken heart but with a tremendous appreciation of life. I remember one evening sitting with him in a restaurant by the water, and he said to me, ‘You know, you should appreciate this. This is our life. This is our marriage. It won’t be like this forever.’ I laughed him off a little bit. Now, in retrospect, I realize that he was saying something profound about impermanence and the importance of appreciating one’s life. I learned from him to appreciate the world as sacred.”